Last week, Adobe Systems announced it would stop making Flash technology for mobile devices and would instead focus on HTML5.

Flash’s end has been predicted for the last few years now, as it is not supported on the iPhone or the iPad. Flash runs on other mobile devices, but Apple products are the Marcia Brady of their kind. If Apple rejects you, you’re kinda sorta screwed.

For many graphic artists who joined newsrooms before the big push for “interactive graphics,” Flash was the first program we used to make web graphics with rollovers. We struggled with the differences between frames and keyframes. We learned that changing a movie clip changed every instance of the movie clip. We cheered when we figured those things out, and then were challenged when we transitioned from ActionScript 2.0 to 3.0.

Don’t take that as a complaint. Journalists pride themselves on being problem-solvers whose job is learning new things. With interactive graphics, there was (and still is) always something to learn. Flash, to me, embodies how a lot of people in newsrooms feel: no matter how fast you try to catch up, there’s always something newer to learn.

Earlier this year, I got to attend SND STL. While there, I met a lot of graphic artists who felt frustrated by Flash’s imminent obsolescence. One guy put it best: “I feel like I spent the last three years trying to learn this program, and now that I’m somewhat proficient, it’s useless. I feel like I wasted my time.”

But I don’t think he wasted his time. Here are a few reasons why:

- It was a decent gateway for people who had never coded before. Flash allowed you to create things the way you were used to creating them in Illustrator. Using ActionScript, you could make those objects do things. ActionScript won’t work in HTML or JavaScript, but the general concept is the same: you have code that dictates what the package looks like and how the user will interact with it. ActionScript and JavaScript are not the same but they have similar structures. You can’t waltz from one into the other, per se, but knowing one could help you grasp some of the basic concepts.

- It forced some people to learn HTML and CSS. When you finished your Flash file, you had to export it as a SWF. To put that on a web page, you still needed to write code that said, “Hey, show this Flash file.” If you had never used HTML before, having to embed your Flash movies might have been your introduction to basic CSS and HTML.

- You proved you could adapt. Remember when we all had to switch from FreeHand to Illustrator? Or ActionScript 2.0 to 3.0? There were quirks and growing pains, and you might have complained that you shouldn’t have to learn this stuff. But you did it. So what if Flash is no longer used by many organizations. The take-away is that you have proven that you are willing to invest time to learn whatever the new technologies are. Spin it that way, and your Flash knowledge makes you look like a hard worker who can try new things, rather than some dinosaur.

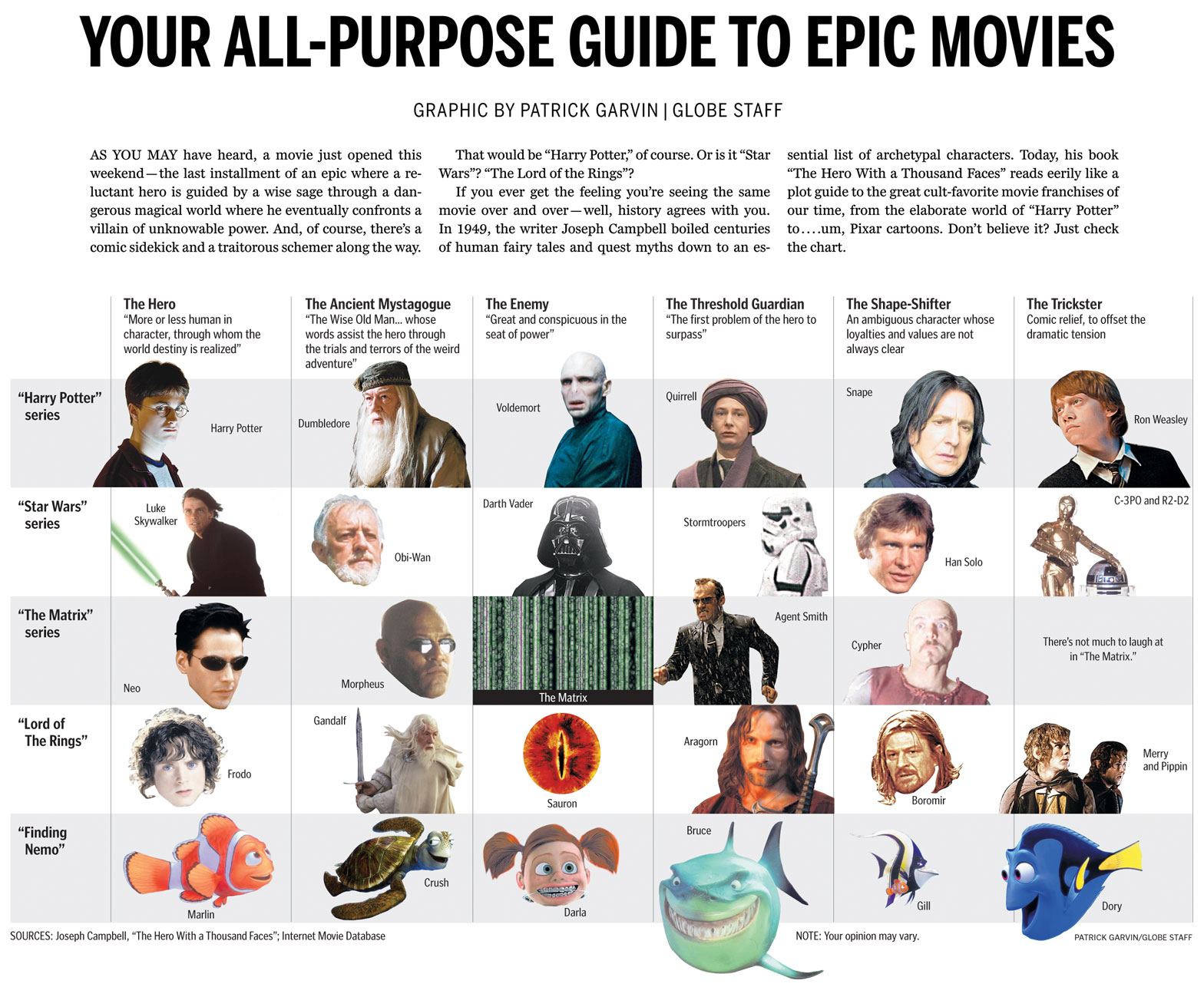

- Understanding the philosophy behind what makes a good interactive graphic is just as important as knowing the specific technology. Page designers who made good pages in Quark figured out how to make good pages in InDesign. The fundamentals of page design didn’t change when we switched from Quark to InDesign. The fundamentals of good information graphics didn’t change when FreeHand was replaced in newsrooms by Illustrator.

The Nieman Journalism Lab had a good piece about how Adobe’s abandonment of Flash will affect the news organizations who used it. If you haven’t seen it, please do.

And then start on your HTML5 tutorials. There are interactive graphics to be made.