Yesterday, President Obama and his wife Michelle visited Ireland. Last week, Queen Elizabeth II was in Ireland. All in all, a pretty big week for the country.

Obama was there pay tribute to his lineage in Moneygall, which Mark Landler of The New York Times described as “a postage-stamp Irish hamlet of 300.” Obama hugged people, shook hands and — most importantly — had a Guinness.

The Queen’s visit was more somber, as she addressed — but came short of apologizing for — the history of violence between England and Ireland. There were several protestors, and the pictures of them are more striking than the photos of the Queen’s visit. To see photos from The Big Picture, click here.

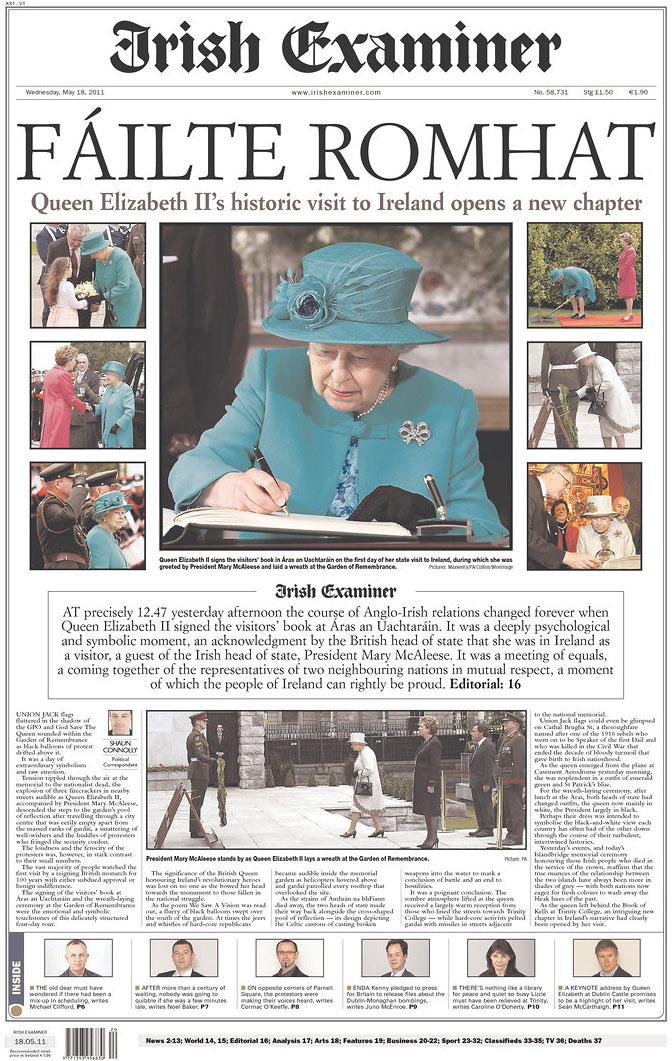

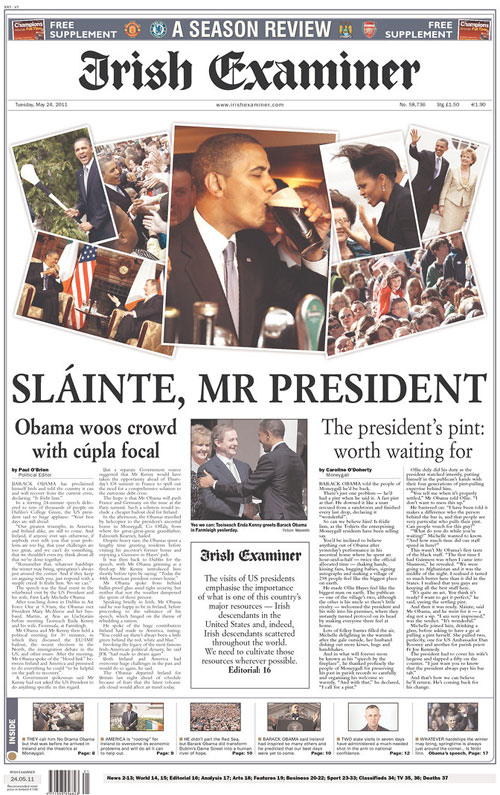

The way the two visits were played in the press highlight the differences of the trips. The usually playful Irish Examiner had a clean, serious front for Elizabeth’s visit, but returned to its normal relaxed form with a scrapbook-y collage of Obama’s visit.

———

THE QUEEN’S VISIT TO IRELAND

The Irish Times focused on the conciliatory nature of the Queen’s visit, showing her with Irish president Mary McAleese laying wreaths in honor of the dead Irish at the Garden of Remembrance in Dublin.

Miriam Lord writes:

This was the moment many thought they would never see.

The Queen of England, standing in the Garden of Remembrance, head bowed in a mark of respect for the men and women who fought and died for Irish freedom.

Here, in this revered shrine to republicanism, the strains of God Save the Queen swelled in the quiet of a Dublin afternoon, played with the full blessing of the President of Ireland and the political establishment.

These electrifying minutes signalled the end of a long and very difficult journey, when two neighbouring heads of state finally stood together as equals in a display of friendship and reconciliation.

To read the rest of Lord’s story, go here.

The Irish Examiner showed several photos of the Queen’s visit, but the largest play went to the photo of Queen Elizabeth II signing the guestbook at Áras an Uachtaráin, the official residence of the president of Ireland.

The importance of this was summed up in the main copy block under the photos:

At precisely 12:47 yesterday afternoon the course of Anglo-Irish relations changed forever when Queen Elizabeth II signed the visitors’ book at Aras an Uachtarain. It was a deeply psychological and symbolic moment, an acknowledgement by the British head of state that she was in Ireland as a visitor, a guest of the Irish head of state, President Mary McAleese. It was a meeting of equals, a coming together of the representatives of two neighboring nations in mutual respect, a moment of which the people of Ireland can rightly be proud.

To read Shaun Connolly’s story, go here.

———

OBAMA’S VISIT TO IRELAND

The Irish Times played the story the way it plays many of its centerpiece stories: with one main photo, one headline and one deckhead. The photos fascinated me, because I was trying to wrap my mind around the glass-looking partition thing from which Obama delivered his speech.

What the Irish Times front didn’t show, though, but did show on its website:

That photo was uncredited on the site. To see that photo (and to read the story by Stephen Collins and Mark Hennessy), go here.

That Guinness moment did make it on the Irish Examiner front, though:

Similarly to the front featuring Queen Elizabeth II, the importance of this event was summed up in the main copy block under the photos:

The visits of US presidents emphasise the importance of what is one of this country’s major resources — Irish descendants in the United States and, indeed, Irish descendants scattered throughout the world. We need to cultivate those resources wherever possible.

To read Paul O’Brien’s story, go here.

———

UPDATE

The Queen did NOT have a Guinness. Read about it here.