Designing web sites and interactives for different browsers is like planning a dinner party for widely different guests. None of whom has RSVPd. You don’t know who could show up, so you have to be prepared that they all could.

The most fickle is Internet Explorer, which is like that guy who was really popular in high school but hasn’t really done a whole lot since then. He invited himself to your party after hearing about it from someone else. He’s nice and well-intentioned, but planning for him is a pain in the ass.

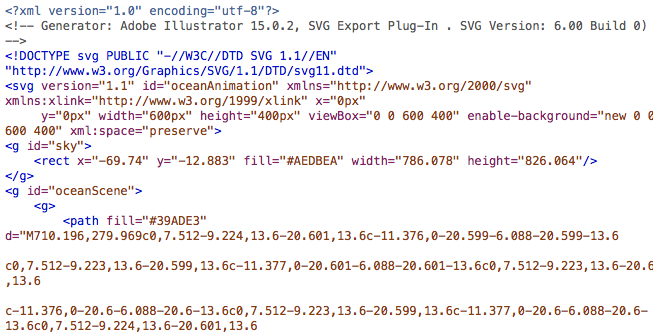

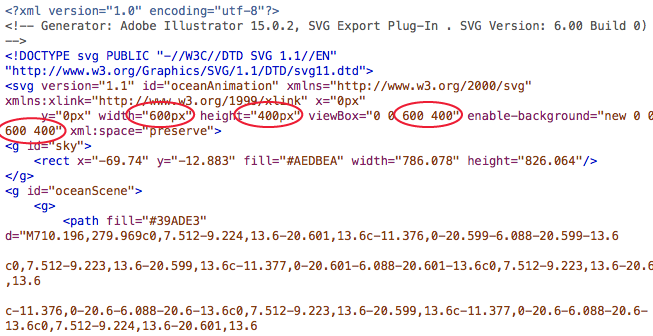

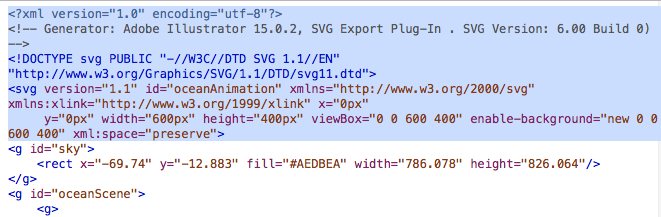

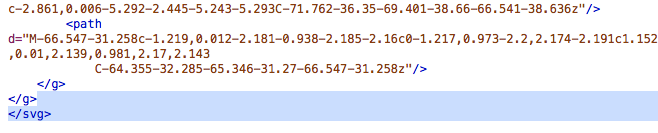

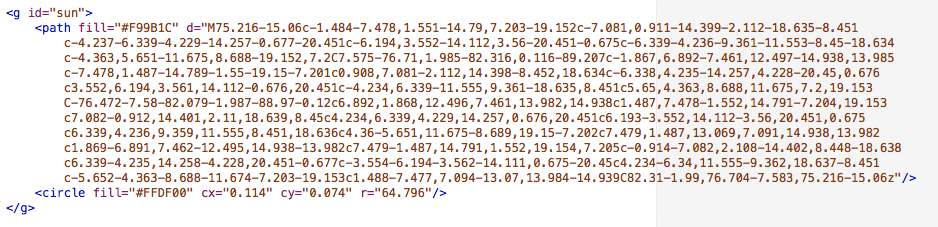

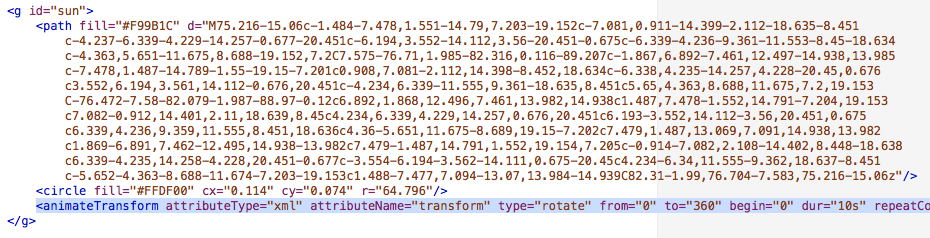

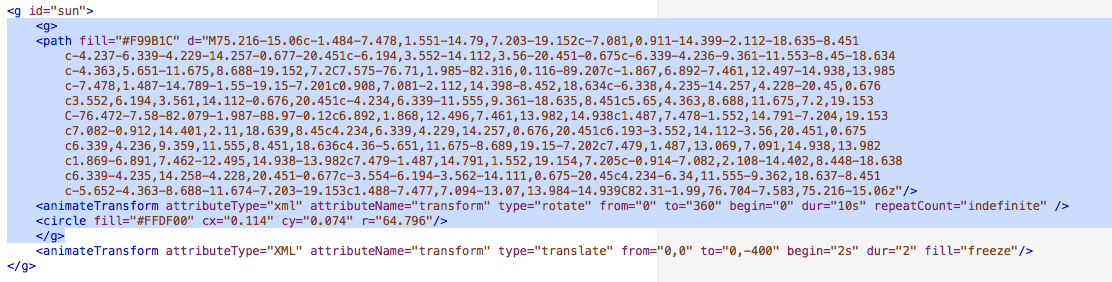

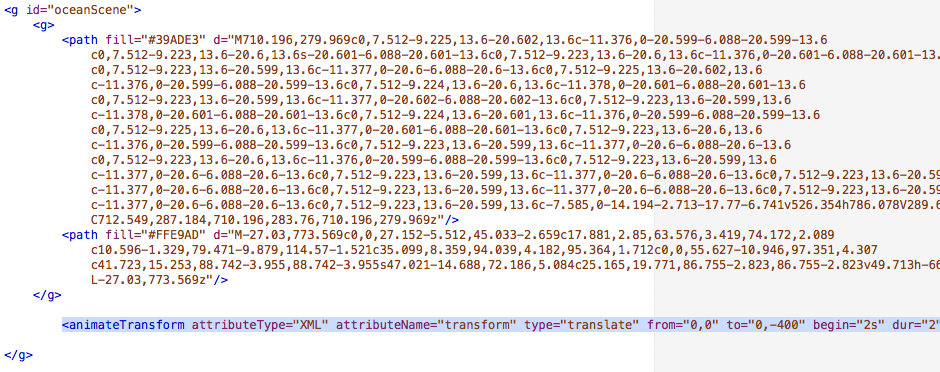

Depending on the version, Internet Explorer can’t handle SVG, and when it can, it needs a lot of special help if you want to animate the SVG. This is the equivalent of a party guest who doesn’t always drink booze, but when he does, it’s Budweiser from a can and he’s hammered by the the third beer.

Beyond that, Internet Explorer can be finicky about aspects of CSS that other browsers can handle without any problem. Like break points in media queries. This is to say that this Budweiser-drinking party guest is also lactose-intolerant, but sometimes drinks milk anyway and then complains about it. He doesn’t eat red meat or chicken, but does eat turkey. He’s allergic to nuts, gluten, oats, soy, baby carrots, cherry tomatoes, white onions, food products made in July, and pickles cut the long way. He can’t eat black beans because they give him horrible gas.

Some versions of Internet Explorer can’t even recognize borders applied in CSS, which is the equivalent of this party guest saying, “Bee tee dubs, I’m allergic to water.”

You can’t just uninvite him, either, because he’s still popular among many circles and you can’t risk the fallout that could come from cutting him off. His retired family members no longer work, but they could still show up and wreak havoc at your party.

He might not show up, but just in case he does, you want to have something he can have. Maybe a jar of gluten-free air.

Much more agreeable is Safari, your bubbly coworker in her mid-20s. Just as Safari shows up in every Mac product, this party guest shows up at every party you have, usually 10 minutes early. Safari handles CSS much better than IE, which is to say that you don’t have to worry about this guest not eating any of your tapas. I’ve noticed in some of my projects that CSS break points look a little rougher in Safari, which is to say that if you ask this party guest to pick up chips on the way, she might just get the store brand chips unless you specify the brand you want.

Where Safari can have issues is the css for animated SVGs. This can sometimes cause Safari to flip out, much in the same way that certain hard liquors will send your bubbly party guest into a blackout drunken stupor where you have to confiscate her phone so that she doesn’t keep texting the guy she met on Tinder.

Firefox is much more capable and reliable than Internet Explorer and probably Safari, but that doesn’t mean it’s not without its quirks. Firefox is that friend you invite to the party because you like him even though he can be kind of a snobby, pedantic smartass. Firefox can handle SVG with aplomb, but I’ve had to use an if/else statement to distinguish whether the user has Firefox, and thus whether to apply different JavaScript. This is like having to make a separate booze run because your contrarian friend insists on drinking a more expensive “specialty” vodka that you can only get at certain liquor stores. He uses terms like “craft cocktails,” and if that didn’t make you roll your eyes, his blog about craft cocktail trends as a symbol of populism in the west will shoot your eyeballs from your skull.

These criticisms so far stem from SVG, but there are more generic irritations with Firefox. There are times I’ve had to add “float:left” to the CSS because Firefox has pushed divs with a 100% width all the way to the right off the screen. This is a quirk that even IE didn’t have. This is the equivalent of asking your friend to pick up ice on the way to the party.

“Can you grab ice? The bodega by my house sells pink bags in seven and 20 pounds. We just need one seven-pound bag. Thanks!”

And then from the store, your friend calls and says, “I can’t find anything like what you’re talking about. All I see are light magenta bags of ice that weigh 6.95 pounds and 19.95 pounds. What should I do?”

“Right now, I wish an actual Firefox, like a fox made of fire, would come and eat your face, you pedantic nerf herder.”

In the grand scheme of things, having to add “float:left” or Firefox-specific JavaScript isn’t a deal-breaker. But those things can make designing web packages annoying, particularly because Firefox is so capable otherwise. This is why Firefox’s quirks can make it more annoying than IE. Internet Explorer, with its myriad food allergies and other quirks, is so demanding that you’ll never be lulled into thinking that you don’t have to attend to it. Firefox’s quirks feel like that party guest who throws a tantrum while the host administers CPR to Internet Explorer because he accidentally had water with an ice cube.

But the browser that gets you through this soirée is Google Chrome. Testing iterations of your responsive interactive graphic on Chrome is like having your BFF at your side for this chaotic gathering of misfit toys. Chrome gets you. Chrome knows you inside and out. And that’s not just because Chrome is synced with your Google accounts and thus literally knows everything about you.

Chrome will call you on the way to your dinner party and ask you if you need her to pick anything up at the store. Unlike the other guests, Chrome doesn’t need any more instruction than “ice” or “chips.” Chrome will get it for you and even get you a six-pack of your favorite beer, because Chrome could hear in your voice that you were a little stressed.

Chrome’s got your back.

Chrome can handle SVG with ease, whether it’s static, animated with SMIL, whatever. This is like having a BFF that’s not picky about beer, wine, or liquor. You could even have bottom shelf vodka that stings like rubbing alcohol and your bestie wouldn’t care.

“What y’all drinkin’ on?”

“Burnett’s.”

“Awesome. Gimme some.”

Now, only every once in a while, Chrome will stall on a page and give you an “Aw snap” fail page. But if you refresh it or try it in another tab, it’s dependable again. That’s the equivalent of calling your bestie and saying, “Hey, you wanna get drinks tonight?”

“I would, but it was a long day, I’m just getting home and I have to be up early tomorrow. But what are you up to tomorrow night? I’m gonna make a casserole and binge-watch the last few episodes of Scandal, drinking Olivia Pope-sized glasses of wine. Wanna join?”

“I’m totes there.”

There are certainly other guests beyond these four, but they aren’t as noticeable at the party. Opera is your friend’s friend who your friend invited at the last minute. You like this guy and think that if you lived in the same city, you’d hang out more. And there are certainly many more Linux web browsers out there. These could be the party guests who came because they were walking by your place, heard the music and knocked on your door. You didn’t prep for them, but they seem cool and you don’t mind if they come in for a bit.

As long as they don’t have weird food allergies.