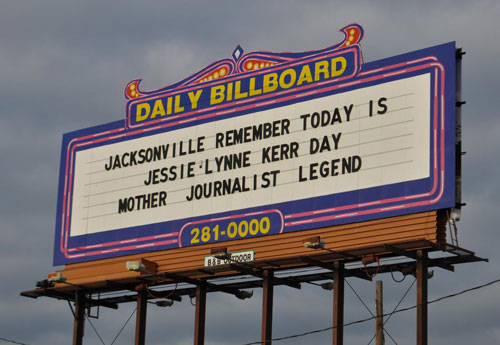

The Jacksonville Association of Fire Fighters have posted a photo on Facebook that’s being heavily re-shared:

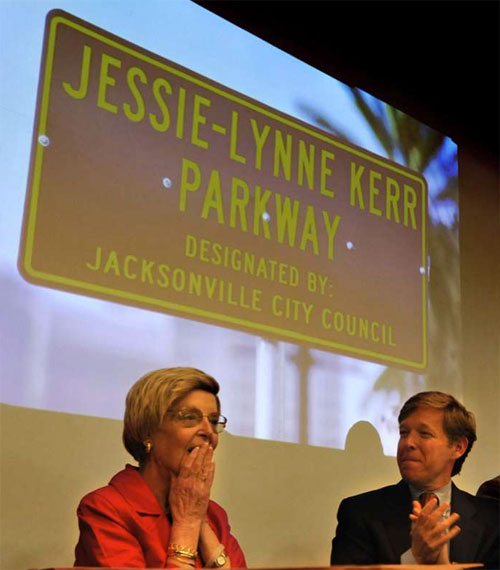

It was year ago today that Jacksonville Mayor John Peyton declared Feb. 22 as Jessie-Lynne Kerr Day, honoring the reporter who worked at the Florida Times-Union for 47 years. Peyton’s declaration was part of a surprise event at the Times-Union to honor Jessie-Lynne’s career. The City Council designated a section of Riverside Avenue as Jessie-Lynne Kerr Parkway, stretching from the Times-Union to Forest Street.

Two months later, on April 28, Jessie-Lynne died of complications from lung cancer. It was two days after her 73rd birthday, or as she would have said, two days into her 74th year.

Jessie-Lynne was a character that fewer newsrooms have now: that curmudgeonly institution of knowledge who had been at the paper longer than many of her colleagues have been alive. She called herself by two nicknames: “Mama Kerr” and “tough old broad.” Depending on the circumstances of your meeting, she could come across as either, or both.

If someone mispronounced Duval County or added more than one L to Philips Highway, we would hear about it. She kept a dictionary on the shelf above her desk, and it came out whenever the word “Caribbean” was used. She’d read the guide on how to say it correctly, though I think she’d read it enough that she had it memorized. But the dictionary gave her authority and proved her point.

But ultimately, she was Mama Kerr, bringing in cookies for birthdays, serving dinner at her son’s fire station, leading newsroom tours. And when the chips were down, she was there.

She was a face of the Times-Union, having been there since March 9, 1964. It was one of her proudest anniversaries.

From a Jacksonville standpoint, she did effect some change. Her story saved the Treaty Oak, effectively leading to the establishment of Treaty Oak Park. She convinced editors to cover a parade for Olympic gold medalist Bob Hayes, which she thought was the first time an African-American appeared on the front page of the Times-Union without committing a crime.

In the later years, she chronicled her cancer, and in doing so, talked about her alcoholism, her divorce and the suicide of her oldest son. She received several letters throughout her cancer treatment, asking when she’d publish her next update in the paper. Even people who didn’t subscribe to the paper would ask me how she was doing.

For the Times-Union newsroom, Jessie-Lynne was a needed icon because she was a fighter. We saw friends and colleagues take buyouts, or worse, get laid off. We saw even larger cuts at other papers, and many of us feared our journalism careers were going to end prematurely. We had thrown ourselves far from home and our biological families, and so we had to rely on each other.

I spent four and a half years of my formative 20s at the Times-Union. In addition to the “what does it all mean” phase of the mid-to-late 20s, I lost loved ones, experienced family health scares and other big life experiences that tend to scare the shit out of you the first time you experience them. Having my friends at The Times-Union to support me meant the world to me, and while I didn’t ever see Jessie-Lynne outside of work, she was still a part of that fabric.

I needed that “tough old broad.” I needed her to give me a hug at times, and to tell me to suck it up at other times. I needed her cookies, and yes, I needed her corrections on pronunciations.

Just don’t tell her I said so.

Patrick Job Well Done